AI and the Pay Gap: The Legal Risks Employers Can’t Ignore

Imagine this: an organisation rolls out a sleek AI-driven performance tool designed to calculate bonuses. It pulls in data on productivity, collaboration, and goal completion, then delivers its verdict; a 15 per cent bonus for one employee and only 8 per cent for another, despite their records looking almost identical. When the results are challenged, the algorithm reveals patterns that seem to penalise certain demographic groups. Suddenly, a tool that promised efficiency looks suspiciously like it is entrenching bias. A frightening question then emerges: who is responsible when a machine makes a discriminatory pay decision?

This is not a futuristic thought experiment. It is a very real dilemma for Australian businesses already experimenting with algorithmic decision-making in performance management and compensation. The attraction is obvious; speed, consistency and the appearance of objectivity. The legal and ethical implications, however, are far murkier. Organisations must now navigate questions that straddle law, technology, and culture, often with little precedent to guide them.

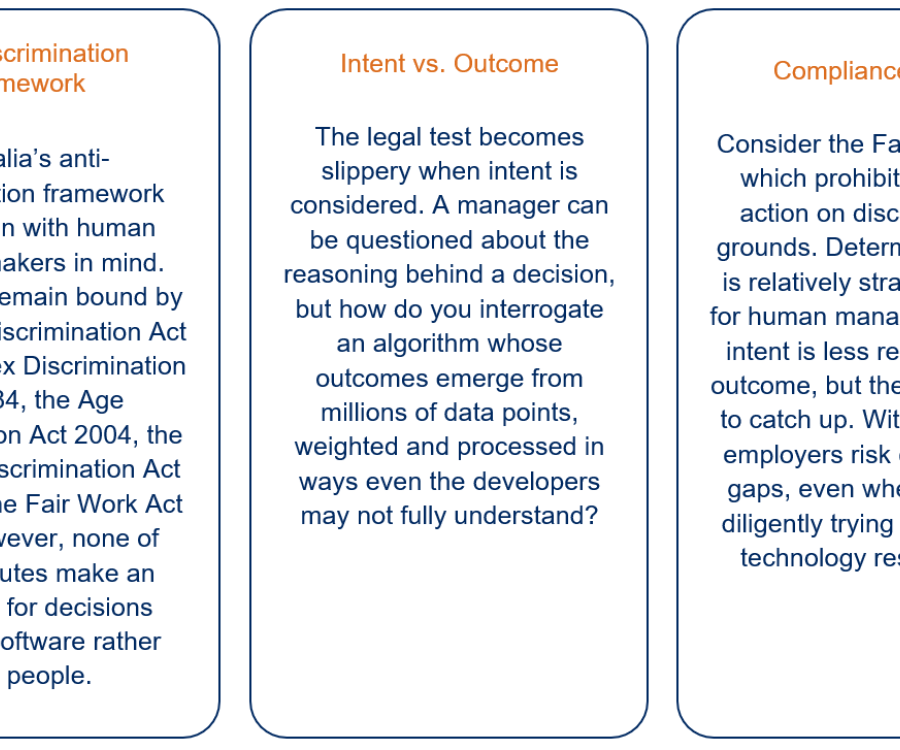

Law Written For People, Not Machines

Bias That Looks Like Neutrality

The danger of algorithmic bias lies in its subtlety. An AI system trained on years of historical performance reviews may replicate patterns reflecting past organisational prejudice. If historical promotions or bonuses favoured particular groups, the algorithm will likely reproduce those disparities. What makes this particularly insidious is the appearance of neutrality. The system applies the same rules consistently, so its outcomes appear objective, even while they are systematically unfair.

Over time, this repetition creates what some experts call “normalised discrimination.” Employees see patterns emerge and assume that consistency equates to fairness. In reality, disadvantage is being hard coded into the system. For affected staff, recognising bias becomes difficult, as discrimination is cloaked in the authority of technology. Managers new to the organisation may never see the original discriminatory decisions; all they notice are consistent, “objective” outputs.

Subtle biases can manifest in unexpected ways. AI may weight communication style, work pattern preferences, or collaboration approaches that correlate with gender, age, or cultural background. A system that unintentionally penalises employees who prefer asynchronous communication or flexible hours may be inadvertently reinforcing inequality. Without oversight, these patterns can persist, embedding unfairness into the organisational fabric.

Whose Hands Are On The Wheel?

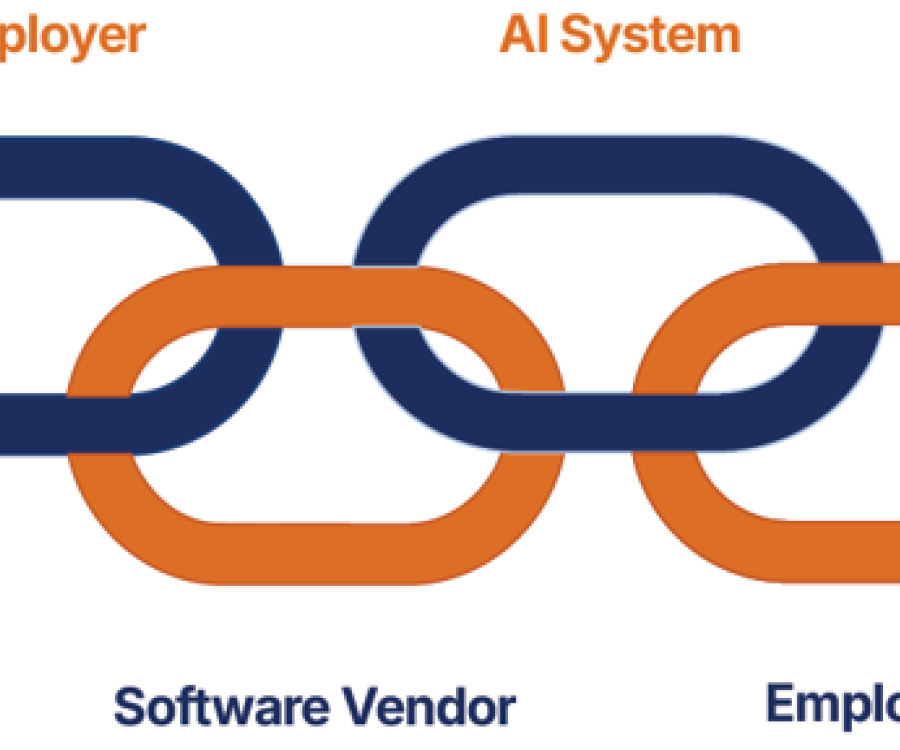

Australian courts have yet to tackle algorithmic employment discrimination in depth, leaving organisations navigating grey legal territory. Employers remain ultimately responsible for employment practices, but the introduction of AI raises complex questions: if an algorithm produces flawed outcomes, is liability solely with the employer, or does it extend to software vendors and developers? Should laws focus on intent when algorithms act independently of human instruction, or should they pivot and assess impact?

The complexity of modern AI compounds the challenge. Proprietary algorithms often operate as “black boxes,” leaving organisations unable to explain exactly how outcomes are determined. Yet transparency obligations remain. Leaders must reconcile commercial confidentiality with the need to provide staff with meaningful explanations.

For now, precedent suggests responsibility rests with employers. Even so, this clarity does little to ease the practical difficulties of explaining, monitoring, and controlling decisions that are increasingly driven by machines.

Culture and Trust on the Line

Legal compliance is one dimension, but the cultural stakes are even higher. Few employees will accept “the computer says no” as a credible explanation for why their bonus is lower than expected. Trust in pay systems is fundamental to workplace culture, and once that trust is undermined, disengagement and attrition often follow.

Transparency matters. Explaining how AI influences outcomes, reassuring staff that human oversight exists, and offering avenues to challenge decisions can make the difference between a workforce that embraces new tools and one that feels devalued by them. Leaders must view AI not as a replacement for human judgment, but as a tool whose output requires interpretation and contextualisation.

The human element remains central. Employees must see that algorithms are part of a system, not the final authority. Clearly communicating this helps preserve organisational credibility and ensures that innovation does not come at the expense of fairness.

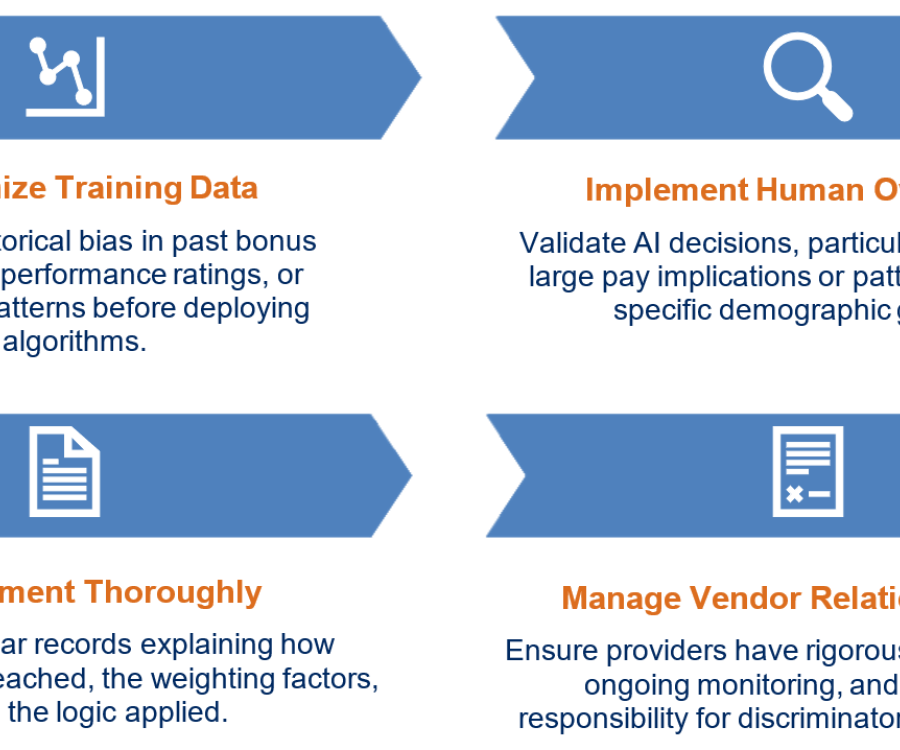

Guarding Against Risk

For organisations using or considering AI in pay, the path forward is proactive, not reactive. Historical bias left unchecked will only be magnified. Leaders should begin by scrutinising the data that trains these systems. Did past bonus allocations, performance ratings, or promotion patterns reflect disadvantages? If so, those patterns need correction before the algorithm is deployed.

Finally, grievance procedures provide a safety valve. Employees must have accessible, human-driven mechanisms to challenge AI-driven pay decisions. Without this, organisations risk eroding trust and engagement.

Australia And The World

Internationally, the debate around AI and fairness is accelerating. Europe’s AI Act introduces requirements for transparency and auditing of high-risk systems, including those used in employment decisions. The Act, which came into force on 1 August 2024, applies directly across EU Member States and includes provisions that specifically address AI in recruitment, performance evaluation, and workforce monitoring. Breaches can result in fines of up to €35 million or 7% of global turnover for serious infringements.

In the United States, several states, including New York and California, have introduced or piloted legislation requiring algorithmic audits or disclosures for automated employment tools. These laws aim to mitigate harm, ensure transparency, and establish accountability in AI-driven hiring and compensation systems.

Canada is also moving toward a regulatory framework through its proposed Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA), which emphasises accountability, transparency, and human oversight in high-impact AI systems. While still in development, AIDA signals a clear intent to regulate workplace AI with a focus on fairness and risk management.

By comparison, Australia is only beginning to outline its regulatory approach, with early inquiries and commission reports signalling concern but offering limited concrete guidance.

The message for employers is clear: compliance expectations will rise. Those organisations that build transparency, accountability, and auditability into their AI processes now, will be better positioned when legislation catches up. Early preparation is not just prudent; it is strategic.

More Than Compliance

Ultimately, the algorithm question is about more than law. It is about fairness, trust, and human dignity. Technology offers efficiency and scale, but without careful governance it can entrench disadvantage under the guise of objectivity.

The organisations that succeed will treat AI as a tool to be managed responsibly, not an oracle to be obeyed. Leaders must ensure that AI enhances workplace fairness rather than hollowing it out. Machines may process the data, but people live with the consequences.

Approaching AI with intentional governance, regular review, and transparent communication allows leaders to harness its benefits while safeguarding employees. This is the frontier of modern remuneration, where technology and human judgment intersect, and where leadership shapes not just pay outcomes but organisational culture itself.